Seven long years of tariffs and China’s economy is still plowing ahead. Outsourcing manufacturing, however, will be a problem for many workers who lose their jobs. It’s something China never really had to deal with. They were the country that soaked up everyone’s labor. Now, because of rising tariffs, Chinese companies are offshoring. It is unclear the number of Chinese workers that have been displaced because of it.

The recently completed “Two Sessions” meeting on March 11 saw Beijing set its 2025 growth target to around 5 percent anyway. It is a number many China watchers are accustomed to. Five percent tends to be Beijing’s magic number. The 5 percent forecast was the same for 2024 and 2023.

A new stimulus package was added to give the consumer economy a push. If China was doing well, it would not need all these rounds of stimulus.

The first two supported the bond markets in November and December. This latest one is 300 billion yuan ($41.5 billion) for consumers to swap old cars and household goods for new ones. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will presumably pay the difference.

Beijing has tried for years to get the local Chinese to spend more on what China makes. When the local economy does not absorb what the local companies make, they end up selling it to their biggest customer—the United States. Geopolitical risks, which began during President Donald Trump’s first term in 2017, have led some American companies to remap their supply chains out of mainland China. In his second term, Trump already increased tariffs on China by 20 percent over the existing 25 percent tariffs. Some tariffs are lower. Some are higher. Regardless, the cost of doing business there is rising for American importers.

To keep their relationship with their U.S. partners, Chinese companies of all sizes and in all sectors have been investing overseas. They are outsourcing labor via contract manufacturing in Southeast Asia, led by Vietnam, or building factories there.

China’s Exporters Investing Abroad

China’s expansion overseas might be good for Chinese companies. It is usually bad for Chinese labor that was once employed by them. These shifts to manufacturing abroad is a headwind for China, which is still a manufacturing, export-driven economy.

Unemployment has reportedly hit its highest level in two years, some three years after the pandemic has ended.

In 2023, the World Bank had urban unemployment rates at 4.7 percent, only slightly lower than the highs reached during the pandemic. China’s unemployment figures for 18-24-year-olds, minus students, began the year at 15.7 percent. The regime has an urban unemployment acceptable rate of 5.5 percent, based on targets set in the latest Government Works Report.

It is possible that some of this unemployment is due to Chinese companies setting up shop in other countries at the expense of the domestic labor pool.

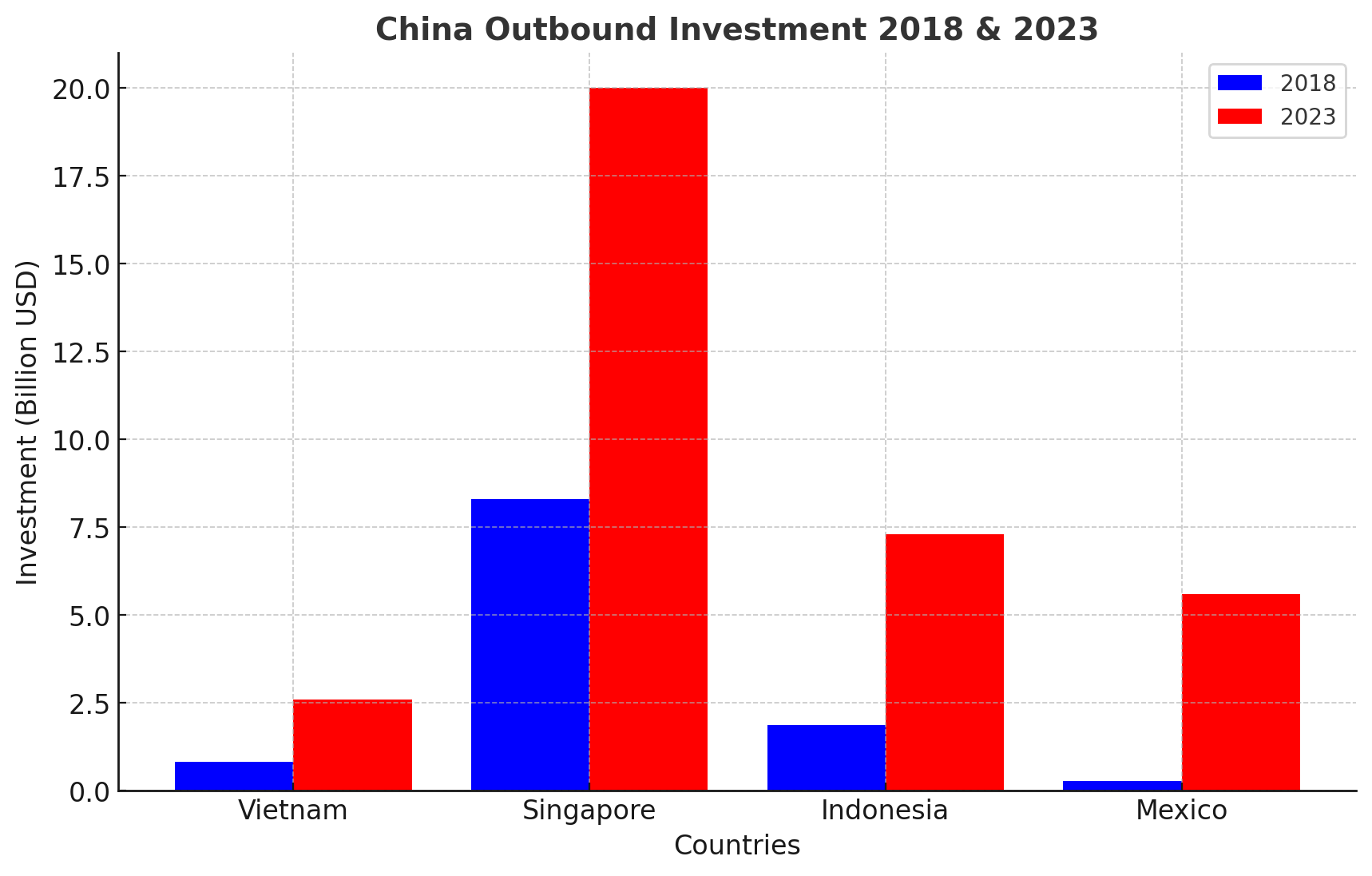

Vietnam has been a big recipient of Chinese capital. Chinese companies invested around $892.9 million in its southern neighbor in 2018, the first year U.S. tariffs were implemented. By 2023, it reached $2.59 billion, according to CEIC data.

Mexico is particularly interesting. According to consulting firm Dezan Shira and Associates’ China Briefing blog, Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Mexico was around $267 million in 2018 and jumped to $5.6 billion by 2023 thanks to large infrastructure projects and industrial sites like the new Hofusan Industrial Park in Monterrey, a four-hour drive from the Texas border. This facility will house companies that make things like furniture and auto parts that were once made in China and exported to the United States.

Singapore’s FDI is likely to be more securities-related and reinvestment than in manufacturing, making Indonesia one of the biggest sources of manufacturing investment for China, according to data compiled by Dezan Shira & Associates.

‘Trade War’ Can Easily Impact China’s Growth

Trump’s new tariff impacts will not be felt by China just yet. Chinese exports to the United States are up, as are factory orders, according to the China Beige Book, an independent New York-based research organization that collects data from thousands of Chinese firms every quarter.

The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), the business intelligence arm of The Economist magazine, said that the additional 20 percent tariff imposed by Trump last month, would reduce China’s GDP by 0.6 percent. But if tariffs go up to 60 percent, a number still being tossed around on Capitol Hill, then the total impact on GDP growth could be as high as 2.5 percentage points over the next two years, the EIU forecasts.

China still has a large market, and a lot of neighbors willing to buy made-in-China goods, which are surely more cost-effective than Japanese, South Korean, or Western goods. China is far from doomed. But hitting a 5 percent growth target is unlikely as the Trump administration seeks to rewrite and redo the global trade system that once favored low-cost imports dominated by China.

Spanish investment bank BBVA said on March 13 that they doubt China will hit the 5 percent mark, but they raised their own growth forecast from 4.1 percent to 4.5 percent.

More details on new China tariffs, if any, will be announced on April 2. If raised, low-end manufacturing of things like textiles and furniture will increasingly move off the mainland. Meanwhile, China will focus on high-end manufacturing and strategic economic sectors like artificial intelligence and network computers used in data centers, among other things.

The question for China will be what will become of the manufacturing labor force now witnessing what Americans went through when China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001—faced with far fewer opportunities for blue-collar labor to climb their country’s socioeconomic ladder. That’s been something Beijing has been able to deliver for a generation. They’re now hitting a speed bump.