Sam Estreicher is a professor of law at NYU School of Law where he directs its Center for Labor and Employment. He served as chief reporter of the Restatement of Employment Law (2015).

Jack Samuel is a tax associate at a global law firm, and the views expressed here do not reflect the views of his employer.

The emergence of gig work is putting pressure on traditional notions of who is an employee and who is the employer. Workers classified as independent contractors rather than employees can lose state and federal protections for wages, overtime, whistleblowing, discriminatory firing, and more. They also lose federal labor law protections for group protest activity, union organizing, and collective bargaining. It is generally assumed that workers not classified as employees under federal labor law also face liability under the antitrust laws if they form unions, go on strike, or try to bargain collectively with those who hire them.

In a recent article, we challenge the assumption that only workers covered as employees by federal labor law are antitrust-exempt: employer classification of workers as “independent contractors,” whether well-founded or not, is irrelevant to the antitrust inquiry. As long as workers provide only their personal services without significant, non-fungible capital investment, they remain laborers for purposes of the exemption from the antitrust laws that permits collective action by workers.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century employers used various legal tools, including federal antitrust law, to blunt the momentum of labor organizing. Notwithstanding that the 1890 Sherman Act was passed to target the monopolistic excesses of large business trusts, courts relied on the vague language of the Act’s prohibition of agreements “in restraint of trade” to issue injunctions against strikers, picketers, and any form of labor action involving violence, social pressure, or “moral intimidation.”

In 1914 Congress attempted to clarify that antitrust law was not meant to police collective action by workers. Section 6 of the Clayton Act—dubbed “labor’s magna carta” by Samuel Gompers, head of the American Federation of Labor—declared that the labor of a human being was not an article of commerce. Section 20 provided that collective refusal to work, picketing, and boycotts could not be federally enjoined under the antitrust laws. At the behest of business groups federal courts pushed back, reading the Clayton Act’s prohibition of the labor injunction narrowly, until Congress enacted the 1932 Norris-LaGuardia Act and finally ended the abuses of the “labor injunction.” In the late 1930s, influenced in part by the 1935 passage of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), the Court established the “statutory labor exemption” from all antitrust scrutiny for actions by “labor acting alone,” not in combination with businesses, in any “dispute concerning terms and conditions of employment.”

The statutory labor exemption is often thought, without careful analysis, to apply only to the workers classified as employees under the NLRA, effectively carving out from antitrust liability only collective activity protected by labor law. Thanks to the 1947 Taft-Harley amendments to the NLRA, that would exclude independent contractors as determined by the common law’s “right to control” test. But the labor-antitrust exemption predates Taft-Hartley, and its statutory basis predates the NLRA. Taft-Hartley left the Clayton and Norris-LaGuardia Acts untouched. And, notwithstanding a line of cases in which the Court declined to apply the exemption to independent contractors selling goods or otherwise in business for themselves, the Court has never held that the common-law “right to control” test delimits the statutory labor exemption. To understand the exemption’s true scope we must turn to statutory language and context. As our article shows, the original meaning of the language used in the Clayton and Norris-LaGuardia Acts clearly establishes an exemption for all workers, not just employees within the meaning of the common law of agency.

An exempt “labor dispute” is defined in Norris-LaGuardia as “any controversy concerning terms or conditions of employment.” Based on this language, the Chamber of Commerce (among others) has argued that “[a] dispute between a business and independent contractors it has retained . . . does not concern ‘employment’ and thus is not a ‘labor dispute’ within the meaning of the Act.” But the Chamber’s gloss on “employment” is anachronistic. “[T]he dictionaries of the era,” the Supreme Court has observed, “consistently afforded the word ‘employment’ a broad construction, broader than may be often found in dictionaries today . . . . treat[ing] ‘employment’ more or less as a synonym for ‘work.’” “Work,” in turn, was treated as a category no less broad than it is now—the same dictionaries did not “distinguish between different kinds of work or workers: All work was treated as employment, whether or not the common law criteria for a master-servant relationship happened to be satisfied.”

This broad sense of “employment” finds support in cases decided at the time the Norris-LaGuardia and Clayton Acts were passed. In cases arising from labor disputes courts at that time routinely used “employee” interchangeably with “worker,” “workingman,” “laborer,” and “labor.” At a time of great labor unrest, courts routinely referred to controversies involving strikes and pickets as “labor disputes” without first inquiring into whether the workers involved were common-law employees—in some cases applying the term to industrial conflict between companies and workers like organ installers, plumbers, and sign-painters who would likely have been independent contractors at common law. We were unable to find a single case in which the distinction between an employee and an independent contractor appeared in a discussion of a labor dispute prior to or contemporaneous with the passage of the Norris-LaGuardia Act. It wasn’t until nearly a decade after the Noris-LaGuardia Act was passed that state courts began to consider whether a labor dispute could exist between independent contractors and the users of their services. There is no reason to believe that as a matter of original statutory meaning the Clayton or Norris-LaGuardia Acts limit their protection to common-law servants.

There are understandable reasons why the definition of covered employee in a given labor or employment statute does not alter the applicability of the antitrust exemption. Labor laws balance competing goals, such as the employees’ right to engage in concerted activities and the employer’s ability to manage the workforce, which may call for restrictions on statutory coverage that are generally irrelevant to the policies of the labor-antitrust exemption, which deals with what labor can do “acting alone,” before any agreements with employers or other users of their services. Agricultural workers are expressly excluded from the NLRA and its protections, yet those workers remain free to form unions and pursue collective bargaining without the intervention of antitrust laws. Supervisors are also expressly excluded from the protection of the NLRA because they generally function as management’s agents, but they can join unions and seek collective bargaining, outside of NLRA protection but free of antitrust liability.

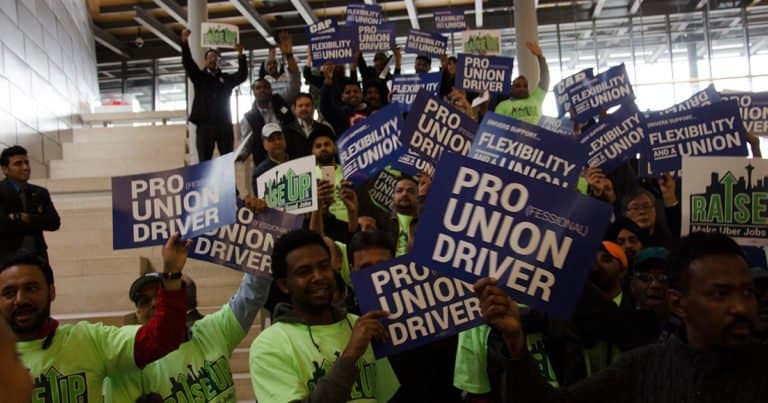

The same is true of gig workers who, although they may be excluded from the protections of the NLRA, are within the shelter of labor’s statutory antitrust exemption. And if such workers are not statutory employees under the NLRA, federal labor law preemption does not apply, which means that states can legislate organizing protections on their behalf without running afoul of either labor law or antitrust restrictions (as illustrated by the 2024 Massachusetts initiative establishing a framework for union recognition and collective bargaining between “ride-hail” drivers and the platform companies). Recognition of the antitrust immunity for independent-contractor workers would mark an important step forward in the economic freedom of these workers, not requiring any statutory change or overturning of Supreme Court precedent, to engage in collective action for their betterment.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

March 28

In today’s news and commentary, Wyoming bans non-compete agreements, rideshare drivers demonstrate to recoup stolen wages, and Hollywood trade group names a new president. Starting July 1, employers will no longer be able to force Wyoming employees to sign non-compete agreements. A bill banning the practice passed the Wyoming legislature this past session, with legislators […]

March 27

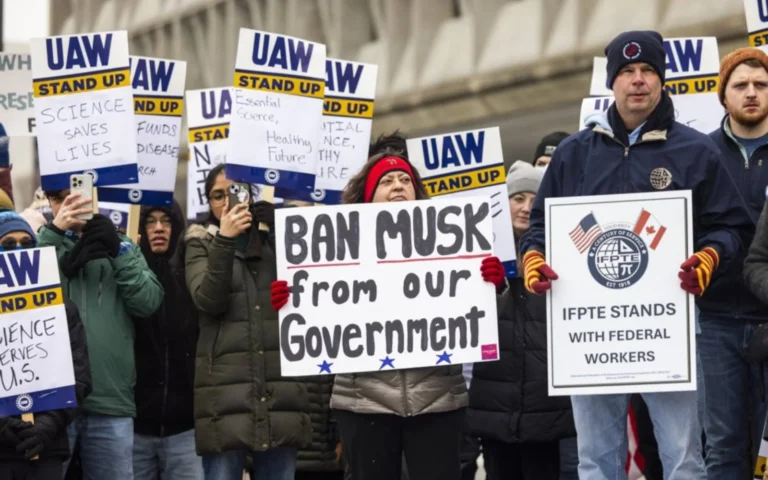

Florida legislature proposes deregulation of child labor laws, Trump administration cuts international programs that target child labor and human trafficking, and California Federal judge reversed course and ruled that unions representing federal employees can sue the Trump administration over mass firings.

March 25

Illinois warehouse quota bill vetoed; Minnesota residents organize; circuit split on NLRB deference continues

March 23

Mahmoud Khalil and labor; CA Fast Food Council's slow start; debating worker-to-worker organizing

March 19

Colorado unions push to join Montana on just cause protection, Starbucks advocates for the Counterman standard

March 16

Trump scraps $15 federal contractor minimum wage, redirects investments away from union-friendly employers; Utah workers launch campaign to overturn ban on public sector unions.