Lockdowns, increased restrictions on out-of-cell time, a lack of rehabilitative services and critically low staffing levels have recently drawn attention to Virginia’s only youth prison: Bon Air Juvenile Justice Center.

Recent public hearings have resulted in officials calling for investigations into the Chesterfield County facility — a potential first step in preventing dangerous conditions from becoming commonplace in the face of chronic understaffing.

Amy Walters, senior attorney and co-interim director of the youth justice program at the Legal Aid Justice Center, said when it comes to Virginia, the juvenile justice system needs to be right-sized.

“If we keep going with these Band-Aid solutions, we don't have to look farther than our neighboring states and what's happening in their juvenile justice communities to see where we're headed,” Walters said.

In an email to VPM News, Department of Juvenile Justice spokesperson Melodie Martin acknowledged DJJ's issues hiring enough staff. She wrote that the agency has participated in hiring events, job fairs, “college and university visits, outreach to military and veteran communities,” and has offered signing bonuses and referral incentives.

But the Bon Air facility's also “utilized specialized staff from the Virginia Department of Corrections to support focused security operations,” she wrote, adding that part-time and contract juvenile correctional specialists are offered “flexible shifts.”

She declined to share how many VADOC employees have worked at the Bon Air facility — or how frequently.

Similar issues are surfacing across the country, as the U.S. Department of Justice investigates multiple states’ juvenile justice systems. In 2024, DOJ found Texas’ juvenile system was violating young people’s constitutional rights and several disability acts. Five facilities faced staffing issues so severe that youth were regularly locked in their cells for 17 to 22 hours a day, preventing both minors and staff from using the bathroom.

Similarly, DOJ is examining allegations of “excessive force by staff, prolonged and punitive isolation and inadequate protection from violence and sexual abuse” against Kentucky DJJ.

At the end of last year, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors declared a state of emergency, allowing law enforcement to be reassigned to a short-staffed juvenile detention hall. If the emergency vote hadn’t passed, the facility was in jeopardy of closing, due to an inability to hire and retain enough employees.

In response to understaffing, states like Ohio are shifting away from incarcerating youth in large prisons and building smaller facilities.

Walters said the issues facing each of these agencies could lead to reconsidering America’s youth incarceration model.

“This trend of not being able to staff these large carceral facilities for youth — somewhat true for adults, too — but for youth, is leading to riots, self-harming [and] homicides,” the attorney said. “I mean horrible, dangerous conditions, and we are seeing ourselves on that trajectory as well.”

A local history

Bon Air Juvenile Correctional Center has long been a symbol of the state’s approach to juvenile justice.

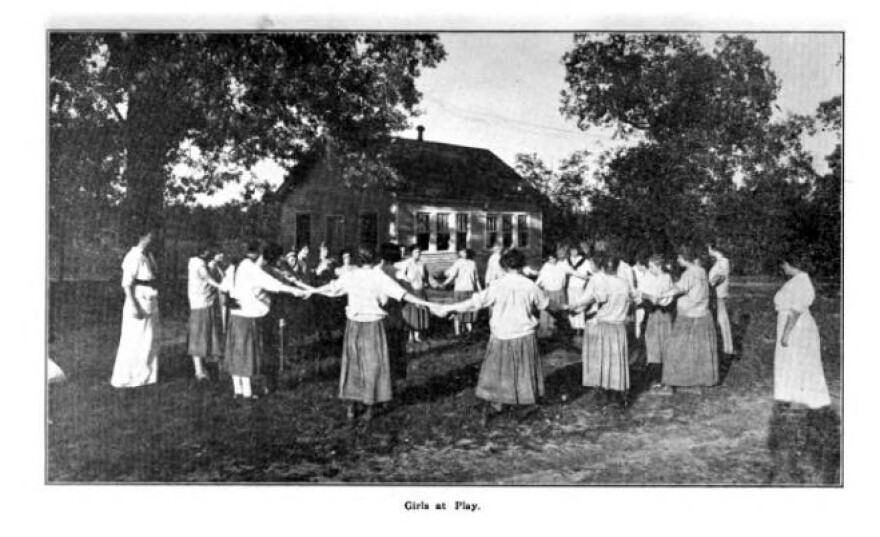

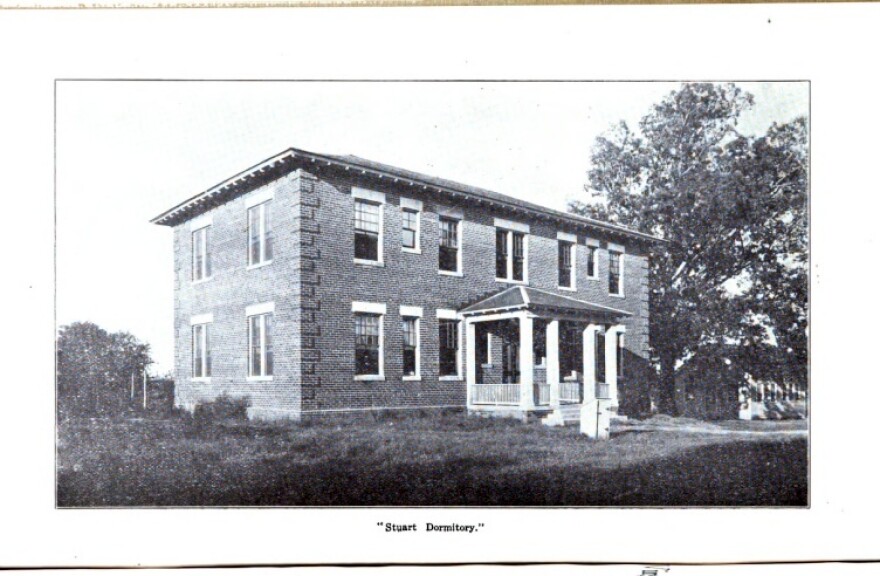

In 1908, land in Chesterfield County was purchased by the State Board of Charities and Corrections, in conjunction with Richmond Associated Charities, to create the Virginia Home and Industrial School for Girls — a juvenile prison for “incorrigible" girls. The facility opened in 1910.

At the time, the white-only reformatory was partially state funded, with the General Assembly allocating approximately 50 cents a day per girl for “the purpose of reforming delinquent girls,” according to Virginia Commonwealth University’s Social Welfare History Project.

Over time, the facility became integrated — both race and sex — was taken over by the state and became Bon Air JCC, Virginia’s sole youth detention facility.

Andy Block, who was director of Virginia’s DJJ from 2014 to 2019, described the Chesterfield facility as being between an adult prison — because of the function it serves in the juvenile justice system — and a treatment center.

“The way that it's like an adult prison is that there's a secure perimeter and locked doors and locked cells,” Block said. “Kids get sent there involuntarily because of their delinquent or criminal behavior. And it's the most secure, deepest end of the juvenile justice system. But where it's very different than in an adult prison is that it's not just about incapacitation, it's about treatment and education and rehabilitation.”

The young people incarcerated at Bon Air range in age from 14 to 20, but children ages 11 to 13 can be held there in some cases, according to Virginia code.

Virginia’s juvenile justice system has undergone significant change during the past two decades, a shift in-line with a national embrace of rehabilitation.

A 2021 study by JLARC, the General Assembly’s research agency, attributed a decline in youth being incarcerated in the state’s system — in part — to DJJ’s efforts, as well as a decline in arrests and complaints from law enforcement, schools or community members.

Reforms, which took place under Block, included closing the Beaumont Juvenile Correctional Facility, reducing the state’s youth facility populations, reinvesting in alternatives to direct care and reforming treatment options.

The study, however, also pointed out several systemic issues within DJJ and at Bon Air JCC — including significant racial disparities and high recidivism rates, calling into question the effectiveness of its rehabilitative programs. The report also pointed out the department’s increasing difficulty in recruiting and retaining staff.

“What we need to be doing in Virginia is going to that data — going back to sort of the underpinnings of this transformation that started in 2014, which was to close all the juvenile prisons in Virginia and create these small regional environments instead, and reinvest in prevention and community-based services,” Walters said.

Looking forward

During her presentation to state lawmakers last week, DJJ Director Amy Floriano said staffing has historically been an issue at Bon Air JCC. She said that she hasn’t been able to find an agency recruitment plan prior to 2022.

“At some point, it's beyond our control,” Floriano said. “We need some assistance and some support in that area. Additionally, the other area that we are requesting assistance is long-term planning for improved locations for better rehabilitation.”

The DJJ presentation noted the root cause of understaffing at juvenile justice systems across the country could be attributed to burnout, low starting salaries, lackluster raises, difficult working conditions, skills mismatches and bureaucratic barriers. However, it did not specifically address the root cause of understaffing at Bon Air JCC.

In a slide titled “Solving Capacity,” the agency noted that one state-run correctional facility is not functional due to there being “no intake or classification space.”

“One facility is not allowing for best practices,” the slide’s next line said. “Confined space not suitable for new programming or therapeutic measures.”

Read part one of “Idleness and boredom” here: Bon Air juvenile center fires point to broader problems

Read part two here: Parents say they're being left out of children’s rehabilitation at Bon Air JCC

Part four of the series will be published next week, focusing on potential solutions to the Bon Air facility’s issues.