When the American Dream crashed and burned: Why Detroit matters to Trump’s tariff narrative

What fueled Detroit's rise as the car capital of the world, and what led to its decline? Why does Detroit's fate lend emotional weight to Trump's tariff arguments?

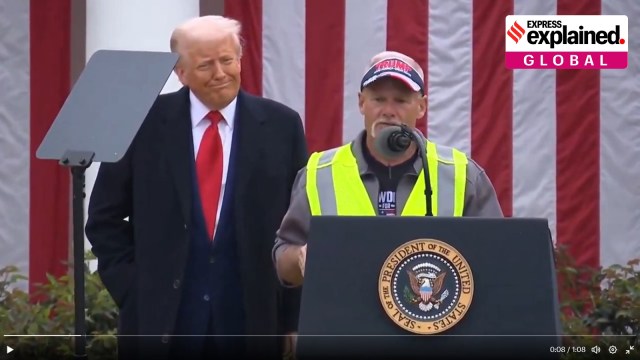

Brian Pannebecker, a retired automobile worker from Detroit, speaks after Trump called him to address the crowd while announcing tariffs last week. (Photo: YouTube/screengrab)

Brian Pannebecker, a retired automobile worker from Detroit, speaks after Trump called him to address the crowd while announcing tariffs last week. (Photo: YouTube/screengrab) When US President Donald Trump announced unprecedented tariffs last week, he said “horrendous imbalances” in trade had “devastated” the USA’s industrial base. He then called upon a retired automobile worker from the city of Detroit, Brian Pannebecker, to “say a few words”.

“My entire life I have watched plant after plant after plant—in Detroit and in the metro Detroit area—close,” Pannebecker told the crowd. “We support Donald Trump’s policies on tariffs 100%.”

For a mascot for manufacturing decline in the US, an autoworker from Detroit, Michigan, is indeed the ideal choice. In scale and in spectacle, nowhere has the American Dream soared and shattered as dramatically as in Detroit. In the early decades of the 20th century, Detroit was the shining emblem of America’s dominance of the automobile industry. The world’s ‘Big Three’ carmakers — Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler — were all headquartered in Detroit. Its most famous music label, Motown, is a play on ‘motor town’.

About a 100 years later, in 2013, Detroit had filed for bankruptcy, beset with poverty, crime, and blight. Since then, the city is recovering, but regaining its glory is a long way off.

Prosperity came on wheels

The founder of the city of Detroit was a French explorer, Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, who in 1701 built a fort on the banks of the Detroit river, and whose name is today synonymous with a luxury car.

Located near the border with Canada in the Great Lakes region (the major lakes of Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario), close to the mining centres of coal and iron, the well-connected Detroit was an industrial city, manufacturing cigars and kitchen stoves in the 19th century. It was towards the end of this century that cars came to Detroit, and from there, shot out to the rest of the world.

Ford’s Model T, which ‘put the world on wheels’. (Photo; corporate.ford.com)

Ford’s Model T, which ‘put the world on wheels’. (Photo; corporate.ford.com)

Automobiles had been around for some time when Henry Ford built one in Detroit in 1896. However, the game changer was the car Ford built in 1908, the Model T. Built using the assembly line production system, the Model T was the first car affordable to middle-class Americans. From here, the car industry took off, bringing jobs and prosperity to Detroit. The two World Wars saw demand soar, with Detroit’s factories building engines, trucks, aircraft, and weapons to earn the epithet of “arsenals of democracy”.

The good times lasted for around 15 more years. By the 1970s, the golden age of Detroit was well and truly over. However, the factors for the decline had been set in motion much earlier.

In fact, a Times article as far back as in 1961 carried this warning — “Detroit put the US on wheels as it had never been before. Prosperity seemed bound to go on forever—but it didn’t, and Detroit is now in trouble.”

Faults in the growth engine

The assembly line system essentially means that instead of workers building a car from scratch, teams of workers perform one task each, with the parts of the car moving around on an ‘assembly line’ from team to team. While this system made production more efficient and cost-effective, it was also boring and de-skilling for workers. One team was doing just one task repetitively, with little creative satisfaction. To make up for this, wages were raised, most notably with Ford’s ‘five-dollar’ days.

The abundance of low-skill-level jobs and the promise of decent pay brought in workers in hordes. “By the mid-twentieth century, one in every six working Americans was employed directly or indirectly by the automobile industry, and Detroit was its epicenter,” historian Thomas Sugrue wrote in his essay Motor City: The Story of Detroit. The thriving job market also brought about unionisation, further guaranteeing salaries and welfare for workers.

However, in the face of this, smaller auto-makers either merged or moved out of Detroit, reducing the number of available jobs. Companies embraced automation, reducing the need for workers. “Between 1948 and 1967—when the auto industry was at its economic peak—Detroit lost more than 130,000 manufacturing jobs,” Sugrue wrote.

To safeguard against strikes, factories were scattered across the city and suburbs: if one plant saw a union strike, production could continue at others. Around this time, in the mid-1950s, building of freeways took off, favouring movement by car, but hitting the development of public transport. This impacted the poorest of workers (who were often Black, but more on that later), who found it difficult to travel to far-away plants for jobs.

Competition from cheaper and more fuel-efficient cars from foreign manufacturers put pressure on the American auto-industry. Even in his tariff speech last week, Trump gave the example of Toyota to show how American products are disadvantaged. Then came rising oil prices and recession.

Detroit had never diversified, all its eggs were in the auto basket. As the industry suffered, so did Detroit, although other factors were exacerbating its problem.

Racism, riots in Detroit

In its boom years, Detroit had been a major destination city of The Great Migration, the movement of Black people from the racially repressive south to the north, in search of jobs and a better life. While they found employment in Detroit — often at the entry-level, least paid jobs — they also found racial tensions, with White people refusing to live or work alongside them.

Buildings destroyed in the deadly 1967 Detroit riots. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Buildings destroyed in the deadly 1967 Detroit riots. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

A product of this was the 1925 Ossian Sweet case, when a White mob threw stones at a house a Black doctor, Ossian Sweet, had bought. Someone from the house fired into the mob, and 11 people, including Sweet and his family members, were arrested. While in a landmark verdict, a jury found them not guilty, Sweet’s wife and brother contracted TB, possibly in jail, and died. Sweet eventually killed himself.

Racial tensions worsened over the years. The comparatively affluent White people moved out to the suburbs, with the spreading out of factories and the building of freeways all feeding into each other. Services like banks and good schools followed the Whites out of Detroit main town.

Meanwhile, with modernisation of the auto industry, the low-skilled Black workers lost jobs. The tax-paying base of the city shrank, impacting civic services like roads, streetlights, cleanliness, fire services, police services, schools, etc. With this, even the better-off Black people moved out into the suburbs. Crime rates soared, and Detroit eventually became the ‘murder capital’ of the US. Matters came to a head in 1967, when the police raided an after-hours bar and arrested 82 Black people. The resultant protests saw violence over five days, in which 43 people were killed and the US Army had to be brought in.

In a perfect example of Gunnar Myrdal’s “vicious circle of poverty”, this led to more White flight, further deterioration of civic services, more racial segregation, and more wealth leaving Detroit.

John F McDonald, economics professor at University of Illinois, wrote in a 2013 research paper (What happened to and in Detroit?), “The years from 1950 to 1970 brought major changes to Detroit. The black population in the metro area more than doubled from 358,000 to 757,000, and the percentage of the population in the city of Detroit that was Black increased from 16.2% to 43.7%… All of this was happening in the other urban areas, of course. However, the city of Detroit experienced a relatively large increase in the percentage black population (to 43.7%) partly as a result of a relatively large exodus of white population to the suburbs.”

In the decades after the 1967 riot, this trend was entrenched, and in 1990, “the Black population of the city of Detroit was 75.5% of the total population of 1.028 million. This percentage is the largest of any of the 17 major urban areas in the Northeast — exceeding even Washington DC (65.2%),” McDonald wrote.

Racially polarised and at times corrupt political leadership of the city did not help matters, with very little attempt at cohesive growth that took everyone along.

While the strong economy of the 1990s, and an emergence of the casino business, briefly improved Detroit’s fortunes, the 2008 financial crisis and recession dealt the city the final blow, with it filing for bankruptcy in 2013.

Since then, civic services have improved and investment has been made to create jobs. Detroit is walking slowly uphill to recovery.

Foreign competition was one factor in the US auto industry’s decline, and the auto industry’s problems were one factor in Detroit’s fall. Trump’s tariffs, thus, may not be the freeway to Detroit’s prosperity.

More Explained

Must Read

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 23: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05